Have you ever heard of saturation diving? Me neither, until I came across a remarkable story, that has been beautifully brought to life in a newly released film.

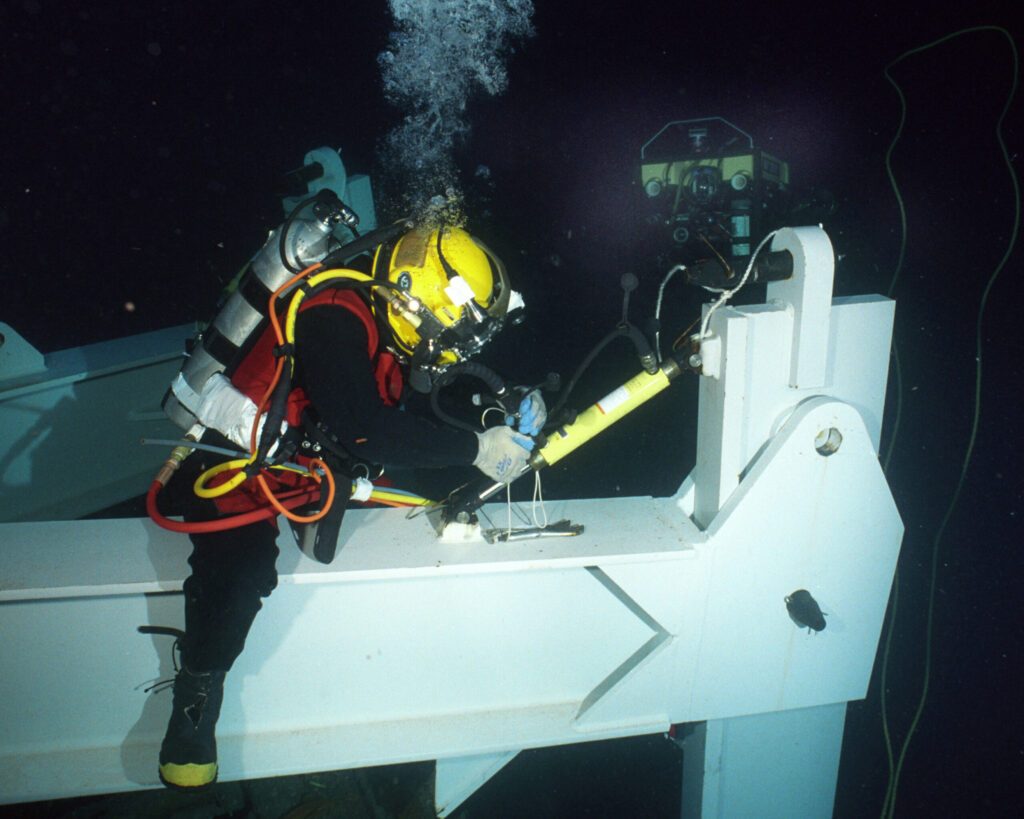

Saturation divers are the brave men who carry out complex technical work in the offshore oil & gas industry—maintaining, inspecting and building underwater infrastructure like pipelines, manifolds and platform legs. The challenge is that they work at depths of around 100 to 300 metres below sea level.

Every 10 metres of depth increases the pressure by one atmosphere compared with the air pressure at the surface. So, at 100 metres, divers experience roughly ten times the pressure we live with—conditions that place enormous demands on the human body and psyche.

At that depth, the gases they breathe are forced into their tissues like water into a sponge. After several days the sponge is “fully soaked” — the body becomes saturated — and from then on, they can only return to normal pressure extremely slowly. If they ascended too fast, the dissolved gases would bubble out dangerously and could kill them.

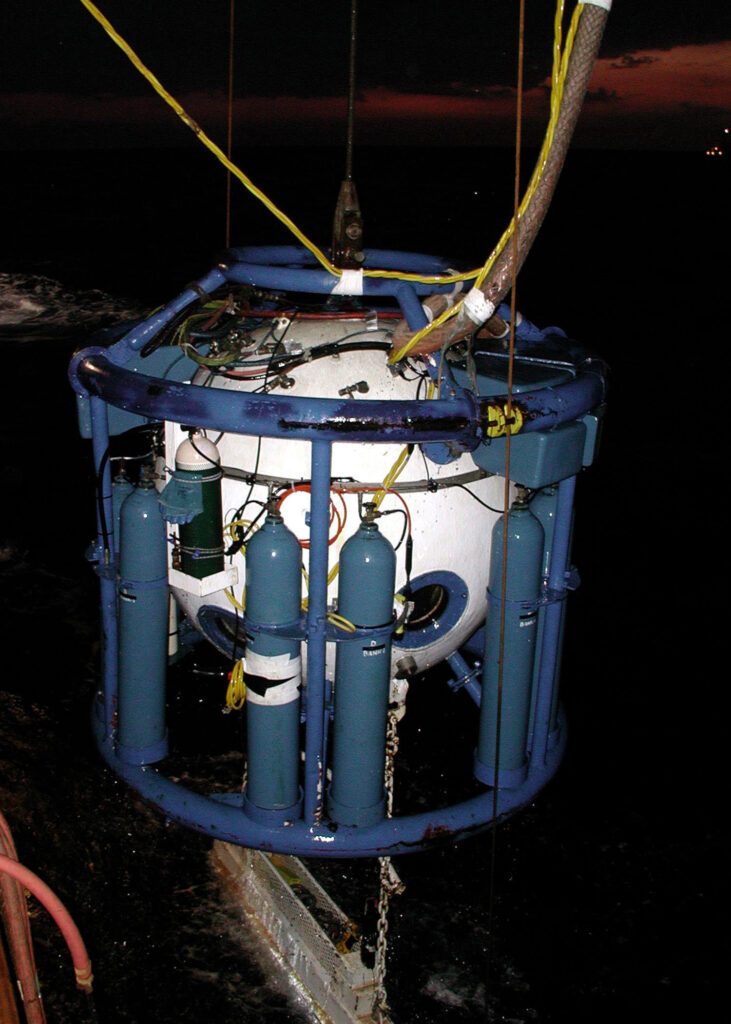

This is why divers must spend significant time in a small, pressurised chamber before they even start their work on the seabed, allowing their bodies to reach this “saturation” state safely. They may live for several weeks in these tight chambers alongside their teammates as the same is required in reverse afterwards, before they can return to the surface. It is treacherous, dangerous and tough.

Once they are ready to work on the seabed, they are lowered toward the construction site inside a diving bell — also known as a diver transfer capsule.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Navy_010707-N-3093M-003_Diver_Transfer_Capsule.jpg

A pair of divers then leaves the bell each connected by an umbilical cord that supplies hot water, breathing gas and communication, while a third diver stays inside the bell to manage and support them. Each shift lasts around six hours before they return to the chamber to rest and recover.

Imagine stepping into a darkness so complete you can’t tell where the sea ends, and your own breath begins. The water is freezing, the visibility close to zero, and the current nudges you off balance with every move. Even with a heated suit and bright lights, you navigate mostly by touch, feeling for pipes and structures in the cold. It’s an environment that gives you no margin for error — only pressure, silence, and a deep trust in your equipment and the teammates who keep you alive.

Now imagine something goes wrong. A violent storm hits the treacherous North Sea, the diving vessel loses power and begins to drift, breaking away from the computer-controlled positioning system. Two divers are working 120 metres below the surface and are ordered back to the bell — but one diver’s umbilical cord becomes snagged on the structure and ruptures, leaving him with only a few minutes of oxygen in a now unheated suit and almost no hope of rescue.

I won’t spoil what happens next.

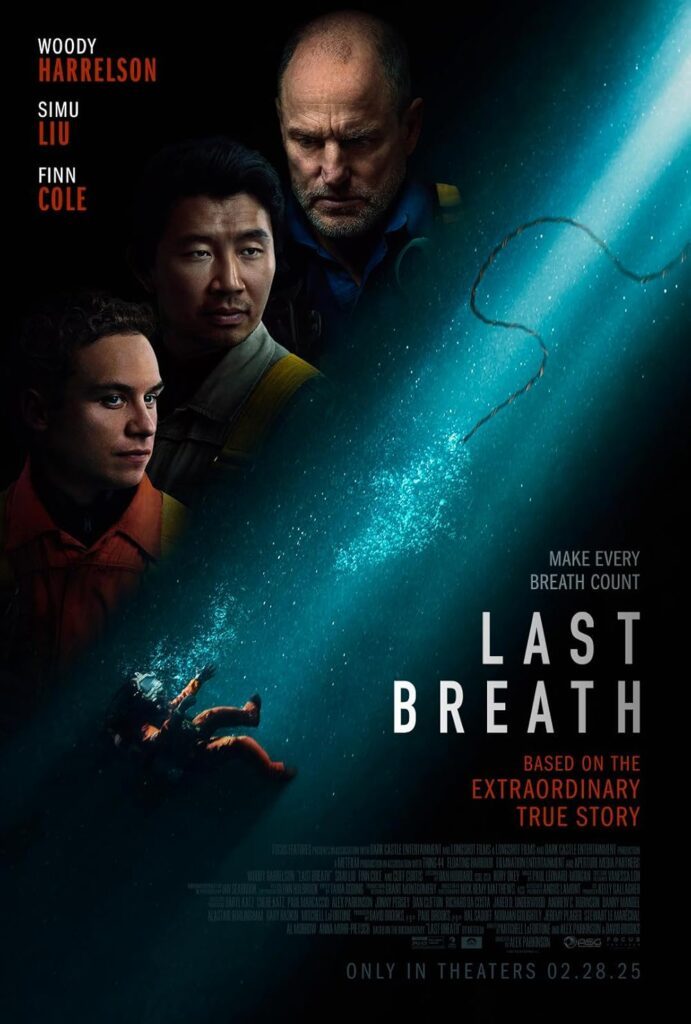

The unfolding of this cliff-hanger is documented powerfully in Last Breath, released this year and based on the 2019 documentary of the same name. What I will say though is that what happens is extraordinary, and the film leaves you reflecting on what it means to keep going when logic says “it’s over”.

As I watched both the original documentary and the new film, a strong parallel emerged for me.

We are now entering the so-called festive season which, for many of us, feels a bit like descending into a highly pressurised dive: so much to finish, so much still to deliver before year end, and only then the chance to “decompress”.

Two things stayed with me from this story.

First, the teamwork around the accident — every crew member supporting the others without calculating the odds. Their unity mattered just as much as the technical challenge and the long compression beforehand and decompression afterwards.

Second, just as every diver needs a careful, gradual process to come out of pressure safely, we also need our own deliberate “decompression” as we move through the year-end rush. Time for rest. Time for reflection. Time for recovery. Because if we don’t make that space for ourselves — who else will?

As the year-end pressure builds and the world around us starts to feel as cold and dark as a 100-metre dive, lift your head, stay connected to your team, and find your own rhythm of decompression — the one that helps you move through this intense period with steadiness, and maybe even enjoy the meaningful work you do under pressure.

And on one of those cold winter evenings, curl up on the sofa to decompress and watch this incredible story. It might just remind you that even in the deepest darkness, miracles can happen — especially when people stay connected and refuse to give up on one another.

Leave a Reply